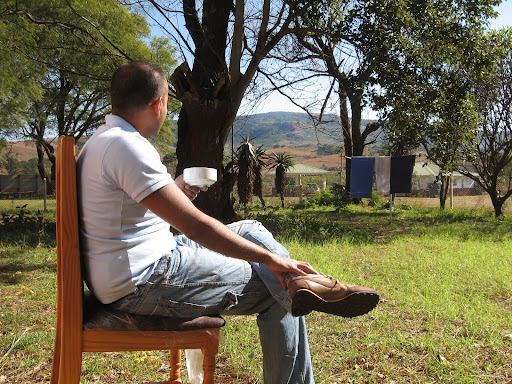

“Did your patient make it to Empangeni?” Hendy asks. It is Wednesday morning and we are drinking coffee on the stoep in the morning sun. I was on call last night. Well, I say on call. OPD was empty by 6pm, we watched a DVD and I was not disturbed again. And to think I was reluctant to come here.

“Did your patient make it to Empangeni?” Hendy asks. It is Wednesday morning and we are drinking coffee on the stoep in the morning sun. I was on call last night. Well, I say on call. OPD was empty by 6pm, we watched a DVD and I was not disturbed again. And to think I was reluctant to come here.“I think so,” I reply, “Why?”

“Because mine got sent back?”

“What?!”

“The ambulance got to the hospital and the strikers turned it away.”

Last Friday was the start of the first big general strike since South Africa went truly democratic. Government employees are striking over an unsatisfactory pay settlement. Hospitals, ours included, have been displaying big posters reminding people that hospital staff are considered "essential" employees (from nurses to cleaners) and are not permitted to strike. Ha!

The cities were affected first and badly so. At the weekend we huddled around TVs watching the news run pictures of people being turned away by picketers outside all of Durban’s biggest hospitals – the ones we rely on for many of our complex referrals. The South Africans in particular felt like they were watching the breakdown of society.

"Patients have died in Jo'burg," one of them tells me. A good friend of hers works at Baragwanath hospital in Soweto - there are armed soldiers on every ward at present because the level of intimidation has been so high. People asked me whether we have strikes in the UK. “Sure” I replied. But nurses? Closing hospitals? It made Britain (where firemen check to make sure the army is ready to take over before striking) seem rather tame.

Hendy and I don’t do surgery so we spent our first day busily identifying problems and getting them out of Ceza quickly. He sent a couple of ladies in labour that were progressing badly to the obstetric referral hospital – they made it through. His lady who needed an evacuation of retained products of conception did not and the ambulance had to turn around. He gets on the phone to Hlabisa to ask one of our colleagues there to do it. I nip to Maternity – yes my patient made it. Because, as it turns out, the transfer happened at 11pm and the strikers had got tired and gone home.

There are no strikers at Ceza. Why not, I ask? The answer comes back: it is “No work, no pay” and in these poor communities that is a threat not to be taken lightly.

Comments